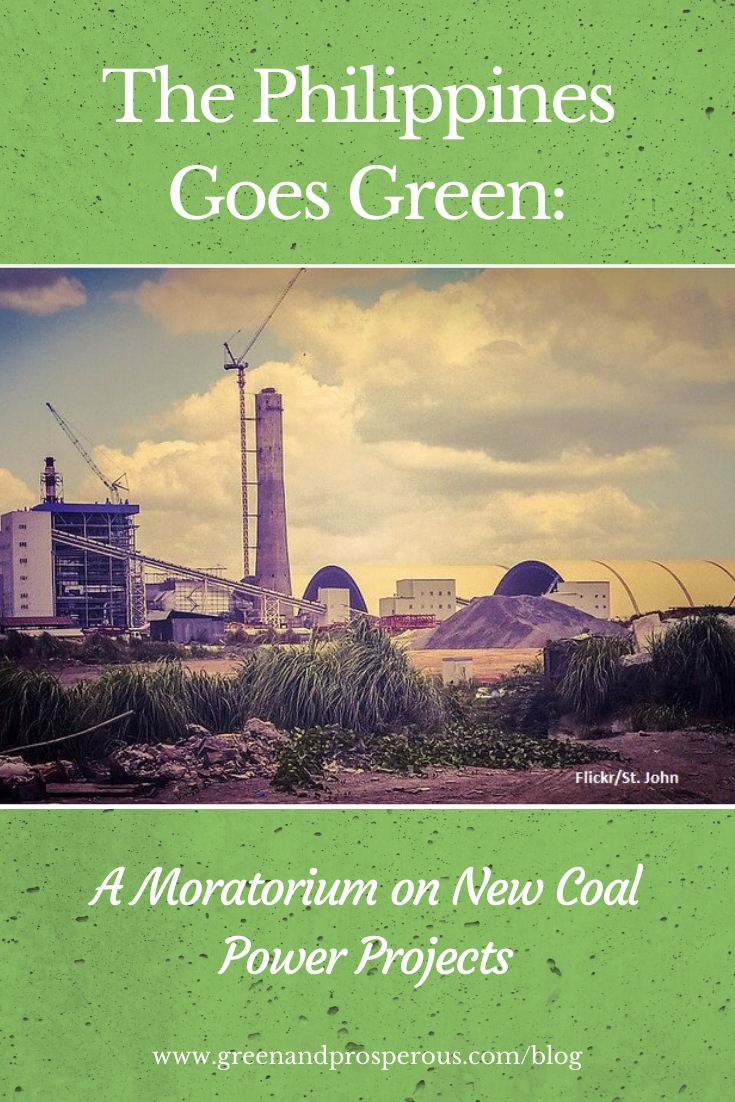

The Philippines Goes Green, Announces Moratorium on New Coal Power Projects

/by Gerelyn Terzo of Sharemoney

Coal is the most common fossil fuel used to generate electricity. In the Philippines, it represents 40% of power production capacity, outpacing all other sources of energy - but it is also the dirtiest.

That’s why the Philippines Department of Energy (DOE) in November 2020 drew a line in the sand and placed a moratorium on any applications for projects on “undeveloped greenfield sites” that rely on coal. Take the Calaca power station, a 900MW coal-fired power plant located in the City of Batangas. It was on course to bolster capacity by some 700MW, plans that were subsequently nixed as a result of last year’s ban.

It was a long-time coming and follows President Rodrigo Duterte’s promise from years ago to incorporate more renewable sources of energy into the capacity mix. The recent move represents a paradigm shift toward cleaner sources of energy including renewables and natural gas for power generation across the industrial, commercial and household segments.

As a result of the ban, 9.6 GW of greenfield coal-fired power generation capacity is on the chopping block. In addition, Energy Secretary Alfonso Cusi has targeted 34,000 MW of renewable energy generation to be in the mix by 2040, with renewable sources poised to comprise two-thirds of the country’s total power generation by then.

The coal ban, which does not include existing projects, comes as developing Southeast Asia’s energy consumption is on the rise, amid a burgeoning middle class that is emerging thanks to higher earnings and disposable incomes. Predictions are calling for a doubling of electricity consumption by 2040, and coal has been the go-to source for power generation across the region.

The tide has begun to turn. Energy finance analyst Sarah Jane Ahmed noted that the Philippines is poised to receive USD 20 billion in investments in the coming decade for renewable energy. Without the capital, the country will have USD 20 billion in idle assets as a result of the ban on coal, she added.

One-Two Punch

In fact, the broader South and Southeast Asian region was previously looked to as the epicenter for coal production, second to China’s massive consumption. A one-two punch of weakened power demand and stalled coal-facility construction as a result of the pandemic, however, threw a wrench into those plans.

Meanwhile, investment banks have pulled back on their financing of fossil fuel power projects amid the Climate Agreement and as investors demand a greater focus on climate-friendly Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues. In addition, the economics for renewable energy production using sources such as solar and wind have been improving, which is making these alternative energies more attractive than coal.

This is especially true considering that coal-fired energy is no longer a cheap power source in the Philippines, as electricity prices are among the highest in the region. This is largely due to the fact that the Philippines imports more than 75% of its coal demand and therefore is vulnerable to the whims of commodity prices and FX rate risks, costs that then trickle down to consumers.

With the ban, the Philippines is following in the footsteps of India, which already slashed a combined 75.8 GW of coal power production in 2019-2020. The trend means that coal is no longer the go-to growth engine it was once thought to be.

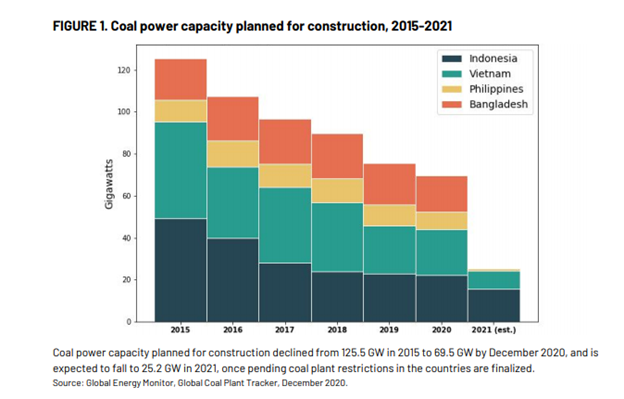

As a result of a decline in new coal-fired power generation in South and Southeast Asia, particularly in the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and Bangladesh, the amount of construction dedicated to coal-fired power capacity is expected to be slashed from 125 GW a half-decade ago to just 25 GW this year, as per the Global Energy Monitor. However, this projected decline also depends on how negotiations go with the sponsors of the power plants.

Walk the Walk

Ayala Corp, which is the oldest conglomerate in the Philippines, has been shedding its exposure to coal power plants in favor of renewable sources of energy. Despite the company’s remaining inventory of a trio of coal-fired power projects, it plans to be fully divested from the dirty fossil fuel by 2030. It is a good thing because as the world moves toward low-carbon emissions, it is expected to become increasingly difficult to secure financing for coal projects.

Since 2015, banks from countries like Japan, South Korea and Singapore have provided close to 50% of the more than USD 50 billion in financing that has been directed toward coal projects across the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and Bangladesh. Now banks like RCBC have decided to end financing to new coal power projects in the Philippines.

Right on cue, Ayala will make the shift to renewable forms of power generation and abandon its previous strategy to invest in coal plants. In the interim, the company will keep delivering power to its customers until it has expanded its capacity in renewable forms of energy. The company’s power generation arm, AC Energy, intends to bolster its capacity to 1,500 MW in 2021, up from 1,100 MW in Q1. In addition, renewables will capture a greater piece of the total pie, rising from 44% to 50% this year.

Separately, Wells Fargo Philippines has recently partnered with AP Renewables, Inc. (APRI), a subsidiary of Aboitiz Power Corp, to help the financial institution bolster its dependence on geothermal power. As a result of the deal, Wells Fargo’s Taguig’s location will receive 7,500 MWh of renewable power from APRI’s geothermal energy plants, which will be “bundled with International Renewable Energy Certificates (I-RECs)”. I-RECs are certificates that verify the energy is coming from a renewable source. It is Wells Fargo’s first foray into geothermal energy, though it already receives all of its electricity requirements from renewable sources.

What’s Next?

The coal ban will remain in place until supply additions to baseload capacity are required in the Philippines, which could be as soon as 2024 for the island of Luzon. And considering that the ban does not extend to existing or approved coal plants, the dirty fossil fuel isn’t going to disappear overnight. In the interim, however, energy sources such as natural gas, geothermal and hydro are likely to become a bigger piece of the country’s power production pie.

Geralyn Terzo (of Sharemoney) is a Wall Street veteran turned financial journalist, having written for InvestorPlace, Motley Fool, and GlobalAg Investing. She also previously served as Sr. Editorial Researcher at MandateWire, MoneyMedia and Financial Times.

Like this? Please pin!